A report in English on everyday discrimination, the double standards of institutions, and the role of Ombudsman Stanislav Křeček.

The “Czechs Only” Case and Institutional Racism in Czech Republic

According to the news portal Romea.cz, a club published on social media a sign with the phrase: “Czechs Only.”

Founded in 2003, Romea.cz is the only independent outlet that systematically documents hate crimes and institutional racism in Czech Republic. Its reports and analyses have become the main reference on discrimination, hate violence, and exclusion, filling a void that mainstream media usually ignores.

Role of the Czech Trade Inspection (ČOI)

The Česká obchodní inspekce (ČOI) classified the sign as discriminatory because excluding customers by citizenship constitutes unequal treatment.

The ČOI is a state body created by Act No. 64/1986 to protect consumers, monitor compliance with regulations, and sanction unfair practices, billing fraud, and discrimination in access to goods and services. In theory, it balances the relationship between citizens and companies; in practice, its actions are selective.

When Discrimination Is Ignored by Institutions

The ČOI sanctioned the “Czechs Only” sign because it was public and impossible to deny.

But when abuses are less visible, the pattern changes. In complaints involving the public company Centra a.s., the ČOI relied on the same formula: “this is not within our competence.”

The problems were not vague. Charges arrived with no breakdown. Fees increased without clear justification. Documents were unsigned. Deadlines were ignored. Tenants were threatened with enforcement. Evidence was submitted.

The replies, however, did not address the substance. Instead, complainants were redirected to civil court (“hire a lawyer”) or to ADR, an out-of-court mechanism that is non-binding and rarely provides real protection.

What followed were template letters, not investigations. No sanctions. No meaningful oversight.

The contrast is clear. When a racist message appears on Instagram, the ČOI moves. When a public landlord mistreats a tenant, the agency retreats behind paperwork.

And when the targets are minorities or foreigners, and there is no media spotlight, the ČOI often vanishes altogether, even in areas that fall squarely within its mandate: unfair commercial practices, misleading billing, and unlawful charges. In these cases, institutional silence becomes the rule.

Everyday Racism Disguised as “Internal Rules

The “Czechs Only” sign was not an isolated incident. Similar scenes play out in everyday life, quietly and repeatedly. Some bars and clubs deny entry to young Roma, often hiding behind excuses like “private event” or “regular customers only.” In housing, rental ads still appear with phrases such as “přednostně pro Čechy” (“preferably for Czechs”), which in practice often signals exclusion, sometimes as blunt as “whites only.”

Online, the same message returns in softer packaging. Posts say “jen pro naše lidi” (“only for our people”), a coded way of drawing a line against anyone with darker skin. These cases rarely end in sanctions, not because they are harmless, but because they happen without cameras and without public pressure. Over time, they create an invisible barrier between “real Czechs” and everyone else, even when the “others” are Czech citizens too.

The Myth that Being Czech Means Being White

For decades, research and monitoring reports have described the same assumption: many people still equate “Czech” with the white majority. The Public Opinion Research Centre has repeatedly shown strong anti-Roma attitudes in the country, and the pattern is visible far beyond surveys.

European institutions and human rights organizations have also documented how Roma are treated as if they were permanent outsiders. In 2021, the Czech state officially recognized antigypsyism as a specific form of racism. The recognition was formal, but the social reflex remained.

That is why the “Czechs Only” message lands the way it does. It sounds absurd on pape, most Roma hold Czech passports, but in everyday practice it is widely understood as a racial filter: “whites only.”

Romea.cz has documented many cases where exclusion is justified with polite language. Shops cite “security” or “internal rules.” Bars talk about “regular customers.” The result is the same: segregation, often open, sometimes coded, and rarely punished.

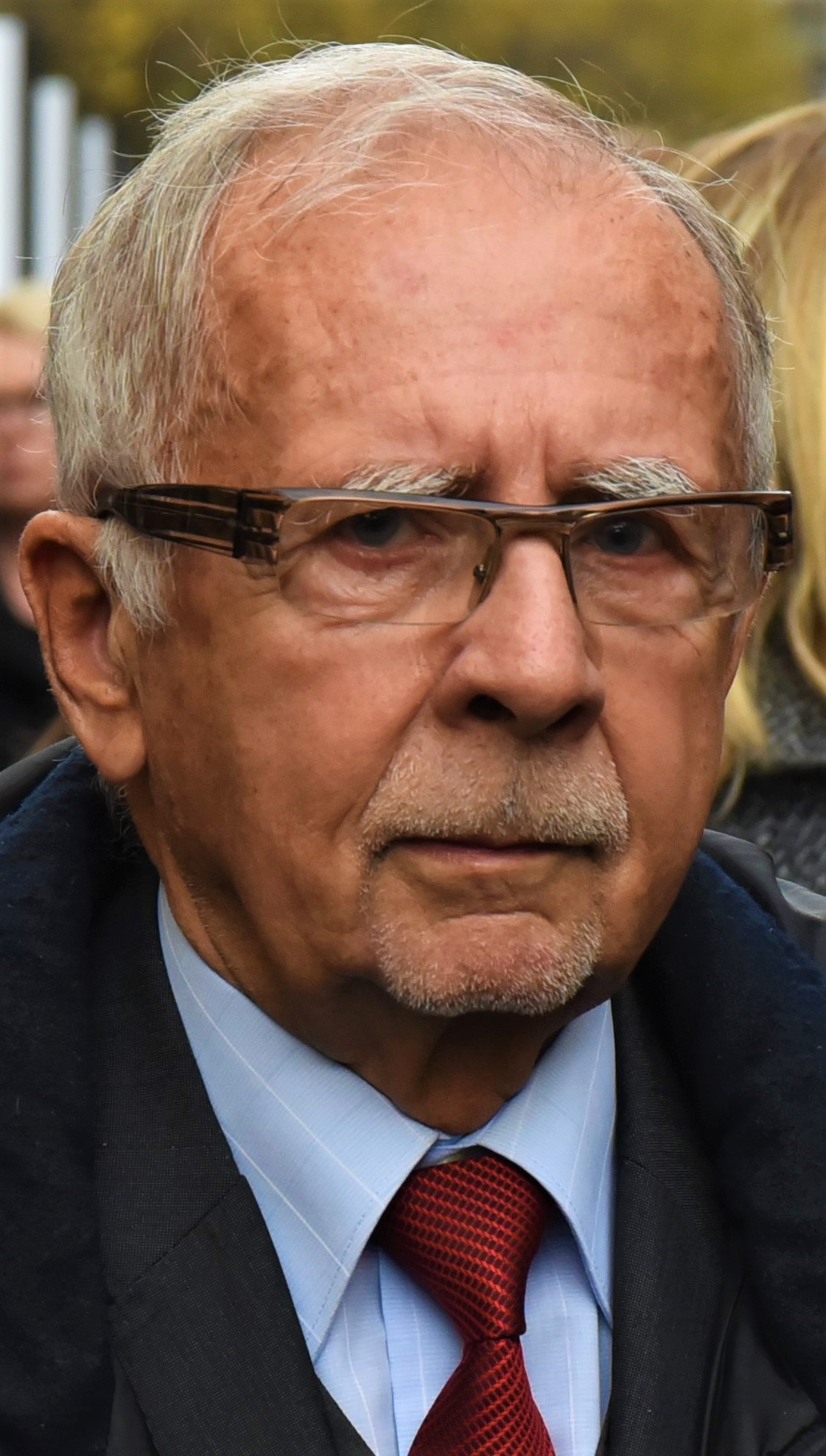

Ombudsman Stanislav Křeček and Institutional Racism

Authorities could dismantle this discrimination, but they do not. Anti-Roma rhetoric wins votes, and many public officials maintain or tolerate it.

A clear example: Stanislav Křeček, an openly racist and xenophobic figure, heads the Ombudsman’s office. It is like putting a fox in charge of the henhouse. He was placed there by politicians who share his prejudices.

Křeček has denied the existence of racism in Czech Republic, minimized antigypsyism, blamed Roma for their exclusion, and attacked human rights NGOs. With such a record, his role becomes a dangerous paradox: instead of support, minorities encounter justification for majority prejudice.

Křeček does not limit himself to Roma. He has also attacked refugees and asylum seekers, portraying them as a threat. He has claimed they “do not want to integrate” and “bring security problems.” Such words belong to a populist politician, not an Ombudsman. The message is devastating: if the guarantor of rights speaks this way, what can victims expect from courts, immigration offices, or the police?

Structural Racism, Not Isolated Incidents

Discrimination is not an occasional anomaly: it is structural. Only the visible is punished—a sign on Instagram—while everyday racism remains untouched in schools, public offices, and politics. The real problem is that institutions meant to protect victims are run by those who justify hate.

Justice That Stays Silent: Courts and Prosecutors

The Czech justice system does not break this pattern either. According to the European Roma Rights Centre and Fair Trials, Roma face discrimination at every stage of the criminal process: police, prosecutors, judges, lawyers.

The case D.H. and Others v. Czech Republic showed that the segregation of Roma children in schools was structural. The European Court of Human Rights declared it illegal in 2007.

Yet the number of cases officially recognized as discrimination remains minimal: only 56 reached the European Court, and just 3 were considered violations.

This judicial silence is more eloquent than any official statement. Without media coverage, the message is clear: for the system, certain victims simply do not exist.