Extremist Voters in Czechia — Who They Are and What Drives Them

Czech politics is undergoing a quiet mutation, driven in part by extremist voters in Czechia who are reshaping the national debate.

The digital laboratory of Czech extremism

In Czechia, the rise of extremist voters cannot be explained merely as a protest vote: behind it lies a finely tuned digital machine — networks of fake accounts, engagement farms and platforms that amplify rage.

According to Europol, one of these networks managed 49 million fake accounts used to manipulate public debate.

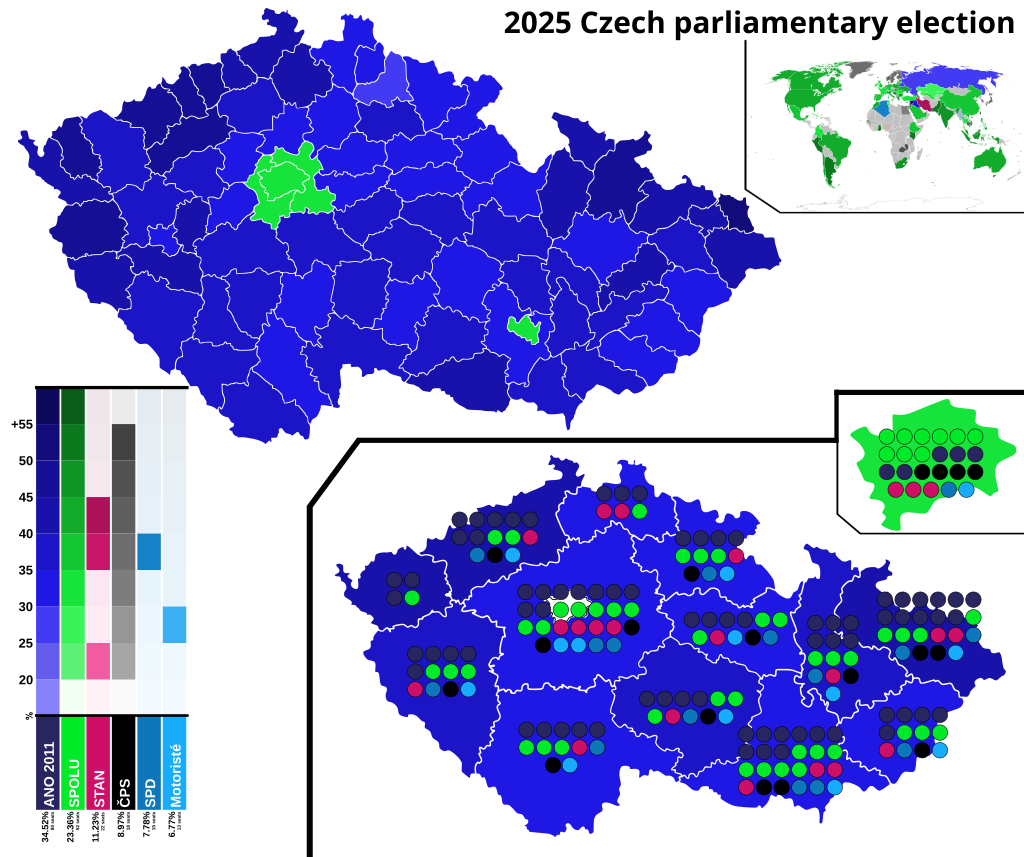

The 2025 parliamentary elections revealed how three populist and far-right parties — ANO, SPD and Motoristé sobě — reached an unprecedented level of representation in Czech democratic history. Those results showed how extremist voters in Czechia turned into a decisive political force, capable of shifting the country’s democratic balance.

A political project disguised as distrust

It is not a spontaneous phenomenon, but a political project disguised as entertainment and distrust. The so-called “nationalists” arrested during the operation had links to pro-Russian circles. As Europol reported, disinformation in this context functions as a weapon: it does not seek to convince, but to exhaust. The more noise, the less truth; the more hate, the less real politics.

When hate becomes mainstream

Meanwhile, traditional parties underestimated the problem. They believed online hate was marginal until it became mainstream. Okamura and Motoristé sobě understood something others did not: on social media, it is not the one who is right who wins, but the one who shouts the loudest. The result is an ecosystem in which extremism no longer needs ideology — the algorithm is enough.

A silent social current

It is not only about parties or campaigns, but about a social current that grows under a façade of normality. In a country without mass migration or major ethnic conflict, hate speech has found fertile ground. What is alarming is not the existence of extremists, but the number of citizens willing to vote for them.

For a broader view of how public discourse shifts to normalise intolerance, see The Overton Window in Czech Politics — a complementary analysis on how the unthinkable becomes everyday.

Roots of a darker mindset

This opinion piece examines who they are, how they think, and why, in a stable and prosperous society, so many choose to embrace ideas that recall Europe’s darkest past. That ideological root, more than a political one, marks the starting point of this analysis.

The imagined purity of extremist voters in Czechia

These extremist voters are not victims of the system; they are its most disciplined believers. They confuse order with virtue, whiteness with merit, obedience with national identity. They see themselves as guardians of an imagined purity and, in the name of that purity, justify the exclusion of others.

Their nationalism does not seek to defend the country; it seeks to reclaim an idealised past — a Europe without mixture, without guilt. They vote for the extremist because he promises that: a symbolic continuity with Germanic greatness, a moral revenge on those who survived it.

They do not hide behind euphemisms; they revel in cynicism. They cite statistics, mock the concentration camps, turn the Holocaust into a joke or an “exaggerated myth.” Their antisemitism is intellectualised, their racism sophisticated. They do not need to burn books — they rewrite them. Reliable institutions such as the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum have long warned about this type of revisionism disguised as “critical debate.”

In truth, they are not voting for a politician. They are voting for a worldview in which power, blood and contempt make sense again. And the most dangerous thing is not their number, but their conviction: they do not doubt, apologise or feel shame.

For further reflection on how hatred moves from ideology to daily practice, read How Hate Becomes Routine in Czech Society — a companion piece exploring this silent erosion of empathy.

Within that same ideological map emerges another profile: the voter of Tomio Okamura — more institutional, but no less extremist.

Okamura’s voters: revenge as political identity

The typical voter of Tomio Okamura is not naïve. They do not ignore the corruption allegations, the murky ties between his movement and shell companies, or the hate campaigns that skirt the edge of criminal behaviour. They know all of it — and still vote for him. Their loyalty, however, is not political; it is identitarian.

For them, Okamura is not a politician to be held accountable, but the spokesman of cultural revenge. He says aloud what many only dare to think in silence: that liberal democracy is a fraud, that foreigners are a threat, and that “national order” must be restored, even if it means sacrificing rights.

This devotion easily survives scandal. While prosecutors investigate SPD’s money-laundering schemes, his supporters celebrate that “finally someone is standing up to the system.” The more he is accused, the more authentic he appears. In their inverted logic, illegality does not taint him — it sanctifies him.

Okamura offers his voters a mirror in which they see themselves as “true Czechs,” heirs to an imagined greatness. His populism feeds not on social promises but on moral purity and shared hostility. Every migrant, every minority, every dissenter becomes a symbolic enemy that holds the group together.

That is why talk of “tunelování” (internal embezzlement) or inflated contracts makes little difference. The nationalist myth outweighs judicial evidence. Okamura’s electorate does not crave transparency; they crave reassurance — and he delivers it, carefully wrapped in patriotic rhetoric and calculated victimhood.

The pragmatic resentment: Babiš’s voters and the illusion of stability

Pragmatism over ideology

At a certain distance, though linked by clear emotional currents, stands the voter of Andrej Babiš — less ideological, more pragmatic, yet perfectly adapted to the same political climate.

Normalising extremism through comfort

Babiš’s voter is not the extremist shouting on social media; they are the one who normalises extremism under the comfort of pragmatism. They see politics as a marketplace and choose the shrewdest manager, not the cleanest one. Their loyalty stems not from affection but from calculation: “at least with him, I know what to expect.”

Fear and the illusion of order

Sociologically, they belong to the lower-middle or ageing middle class — a segment bruised by inflation and wary of change. They fear Brussels, they fear chaos, and they even fear migrants they have never met. Yet, above all, they fear losing the fragile stability of their everyday life. For them, an authoritarian promise of order feels safer than a liberal system that speaks of rights.

Strategy disguised as management

Babiš understands that anxiety well and turns it into strategy. He dresses it in the language of business: “efficiency,” “control,” “results.” To his voters, these words sound more concrete than “democracy” or “solidarity.” And when the far-right narratives of SPD or Motoristé seep into public debate, they do not reject them — they absorb them as background noise, as a necessary exaggeration to keep the system in check.

Resignation as political logic

Deep down, their vote is an act of resignation — better the devil you know. It is the generation that watched the promises of the 1990s crumble and now sees politics as a reality show of power and punishment. That is why Babiš’s technocratic populism blends so seamlessly with the coarse nationalism of his allies: both offer emotional security, packaged in distrust toward the other.

The voters of Motoristé sobě: from everyday fatigue to the politics of resentment

Beyond this circle, populist rhetoric mutates again — this time under a different banner: Motoristé sobě, a movement born from post-Covid fatigue that turned everyday frustration into political identity.

Voters of Motoristé sobě are a typical product of post-Covid Czech distrust — middle-aged men, self-employed or technical workers who feel abandoned by urban elites and traditional parties. They identify neither with modern liberal values nor with old-style conservatism. Instead, they crave a new kind of authority — one that validates their anger.

A culture of distrust and controlled anger

At the same time, their relationship with the state is one of functional hostility. They pay taxes and follow the rules, yet remain convinced the system exploits them. The rhetoric of Macinka and Rajchl — against restrictions, against Brussels, against “green bureaucrats” — channels that simmering rage. It is an electorate that confuses control with freedom: wanting fewer rules but harsher punishment for others.

Socially, this group consists of truck drivers, small indebted entrepreneurs, logistics workers, retired police officers, or employees trapped without social mobility. Moreover, they distrust mainstream media and rely instead on closed online circles or “alternative” channels where conspiracy theories blend freely with patriotic slogans.

From grievance to political revenge

Psychologically, they are marked by a deep sense of grievance and a low tolerance for ambiguity. Diversity, inclusive language or political complexity unsettle them. Consequently, they prefer simple answers: “clear culprits, quick punishments.” Their rhetoric swings between paranoia and moral self-affirmation — “we are the only sane ones.”

Macinka feeds that narrative skillfully. He portrays himself as the champion of “ordinary workers” standing up to “progressive idiots.” In doing so, he gives form to a culture of resentment disguised as national pride. These voters are not searching for leaders but for avengers — people willing to shout what they themselves cannot say at work or at home.

As a result, the outcome is a highly emotional, volatile electorate living in a permanent state of cultural war, eager to punish with its vote more out of impulse than conviction. They do not seek durable solutions, only the fleeting satisfaction of revenge. That emotion — anger wrapped in patriotism — is the true engine driving Motoristé sobě.

Shared roots of distrust and resentment

At first glance, Babiš, Okamura and Macinka may seem to play in different leagues. Their public images differ, their tones vary, yet their voters breathe the same political air — distrust toward liberal democracy, fascination with authority, and rejection of difference.

They are bound not by doctrine but by emotion: resentment. Babiš’s voter seeks control; Okamura’s pursues moral superiority; Macinka’s craves revenge. Within this same ecosystem emerges Filip Turek, born from Motoristé sobě yet reshaped into his own phenomenon — the youthful face of authoritarianism that no longer feels the need to apologise.

The normalisation of intolerance

Okamura gave structure to what Turek merely performs: the legitimisation of hate as political language. What in Turek is provocation, in Okamura becomes strategy; what in Macinka is resentment, in Babiš takes the form of managerial pragmatism. Different styles, same outcome — the normalisation of intolerance.

Danger of hate as social routine

None of these extremist voters live on the margins or under real threat. They inhabit a stable, safe, and overwhelmingly white country, yet they seem to need an enemy to feel alive. Each election, therefore, becomes less an act of choice and more an act of exclusion. And in that transformation lies the true danger: hatred turned into social routine.

Czechia as a political laboratory

The resulting picture is unmistakable — Czech politics has become a laboratory where authoritarianism no longer hides; it merely changes its form.

Risk of a democracy without shame

If this convergence consolidates, Czechia will not turn fascist overnight. It will simply hollow out from within. Institutions will continue to function, elections will be held as usual, but democratic consensus will erode step by step: lies will be tolerated, exclusion justified, and firmness confused with hate.

What was once unthinkable will become routine. And when that happens, no dictator will be needed — only a majority that has lost its sense of shame.